By Melody Songer

Melody Songer is an art major and journalism minor. A student this semester in the Installation Art class with Carmen Papalia, she wrote this article for a journalism class with Professor Cheryl Spainhour.

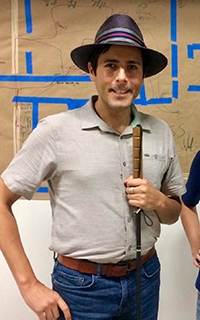

On the first day of Installation Art class at UNC Charlotte, students sit in their plastic, paint-ridden chairs in anticipation. Waiting for their two professors, the class quietly looks over to the tattered walls and concrete flooring, only to eventually discover their teacher has been sitting right next to them all along. Carmen Papalia, a blind social practice artist, dressed in a black fedora and slick vest, uses his long, black cane to locate the front of the classroom to introduce himself.

Papalia, this semester’s McColl/UNC Charlotte Artist in Residence, started creating art during high school in Vancouver, Canada, where he grew up, becoming especially fascinated by two-dimensional animation. He believes that he’s always been a non-visual learner, though he didn’t lose his vision until his early twenties. When Papalia first bought his cane in 2005, he started experimenting with social dynamics within his position as a disabled person. By obstructing his friend, Elliot’s, vision, hearing and mobility with a humongous, blocky sign that read “disabled,” Papalia discovered that disability experiences are just about having a different accessibility.

Papalia, this semester’s McColl/UNC Charlotte Artist in Residence, started creating art during high school in Vancouver, Canada, where he grew up, becoming especially fascinated by two-dimensional animation. He believes that he’s always been a non-visual learner, though he didn’t lose his vision until his early twenties. When Papalia first bought his cane in 2005, he started experimenting with social dynamics within his position as a disabled person. By obstructing his friend, Elliot’s, vision, hearing and mobility with a humongous, blocky sign that read “disabled,” Papalia discovered that disability experiences are just about having a different accessibility.

“I thought of [Elliot] as a stand-in for me and how I was, kind of, navigating this label and how other people were interpreting me,” says Papalia, during a recent interview at UNC Charlotte. “At this point I had to make the choice to not let vision be the goal or central reference point in my learning experiences and the way I understood things.”

His first socially-engaged project blossomed into his life’s work and created the basis for his Open Access methodology, a conceptual framework centered on “care, mutuality and the responsibility to disrupt the conditions that obstruct agency for those in need.” He started creating projects intended to critique institutions that marginalize people. In doing so, he encouraged reorganizing accessibility, so that all types of people and their situations are individually addressed, rather than broadly grouped and given one solution.

The first of these critiques is present in the use of his cane - now filled in with black in response to the white color and red tape placed on it. By design, a cane’s white color and red tape are both used to indicate a blind person’s impairment. But they also invite help that may not even be desired: “I actually felt like the times I was offered support were more of an inconvenience to me…and gave people a license to cross that personal space boundary,” Papalia says. “I felt like this [cane] I decided to use was separating me from my peers, like it was identifying me as someone different. I just really wanted to play with those dynamics, like the project with Elliot.”

Because of his love for walking, especially in new cities to learn their routes, Papalia began leading what he calls “Blind Field Shuttles.” These walking tours emerged from an experience he had while in the Ape Caves in Mt. St. Helens, Washington. Papalia recalls how he independently and successfully navigated the caverns, sliding into their highest spaces and trekking over lumpy cave rocks. Wishing to share that sense of accomplishment with others, and to encourage others to exercise their own non-visual senses, he invited interested visitors to close their eyes and follow him on hour-long walks.

“People have panic attacks sometimes…and it’s because I think when you shut your eyes, you have to deal with yourself,” Papalia says chuckling. “But I’ve had some really great experiences in my walks. Usually people come out at the end of the experience with a sense of accomplishment – like they learned how to do something differently, and there’s excitement in that.”

Papalia held walk in uptown Charlotte on October 15 for students and interested newcomers, starting at the McColl Center for Art + Innovation, where he is an artist-in-residence, and traveling along Tryon Street to the Bechtler Museum of Modern Art. Most of his UNC Charlotte art class, including his co-professors, Janet Williams and Tom Schmidt, attended.

Drew Roland, a student at UNC Charlotte, says Papalia is an inspiration. “He’s a great example of someone who didn’t let their disability destroy them. He’s not using it as an excuse to not move forward – like I can do it, but I can do it a different way.”

Roland and Professor Williams both agree that Papalia has opened discussion on a topic that students usually wouldn’t think about. “He asks you to put yourself in situations and think about how you could improve them, interact with them, what changes might you make,” Williams says, emphasizing his ability to broaden perspectives on accessibility. “It’s just great having McColl artists here because it exposes students to practicing artists working on their own, and he’s an interesting case.”

Papalia and students in the Installation Art class are creating an exhibition called “Close Your Eyes,” which will open in the Side Gallery and the Installation Studio in Rowe Arts on Monday, October 30. An artists’ discussion at 4:00 pm will be followed by a reception from 5:00 to 7:00 pm.